Hazaribagh is nestled in the Chhota Nagpur plateau of Jharkhand, a land where natural beauty blends with cultural heritage. If one has to envision Hazaribagh, then imagine it as a place covered in dense forests and lakes. The name ‘Hazaribagh’ literally translates to ‘Thousand Gardens’ and describes the greenery covering every corner of the district. With 45% of its area covered in forest, the fertile land supports various agricultural activities, contributing to its garden-like appearance.

Hazaribagh is also known for its significant mineral deposits, including coal, mica, and iron ore, which support the local mining industry. However, this mineral wealth contrasts sharply with the area’s poverty and underdeveloped infrastructure. Despite its natural and mineral riches, many residents struggle with poverty, limited access to education, and insufficient healthcare services. The district, with a population of approximately 1.7 million and a literacy rate of about 70%, shows signs of progress but faces challenges related to socio-economic development. The situation is exacerbated by water scarcity, a pressing issue in Hazaribagh, worsened by seasonal changes and inadequate infrastructure. The district relies on rivers, ponds, and wells, many of which dry up in summer. While efforts are being made to improve water management, ensuring year-round access to safe drinking water remains a significant challenge.

Beyond its natural beauty, Hazaribagh is steeped in history and tradition and dominated by tribal communities such as Santhals, Mundas and Oraons. The area is known for its rich tribal culture and traditional crafts, including handwoven textiles, mica crafts, and woodwork, which add to its charm.

Embracing this spirit, Narendra Mahto from Jan Sahyog Kendra warmly welcomed the Rebuild Team to the Land of a Thousand Gardens.

Jharkhand, which was carved out of Bihar in 2000, was created to protect the cultural heritage, identity, and rights of its tribal and forest-dwelling communities over land and forest resources- their jal, jangal and jameen (water, forests and land). Approximately 30% of Jharkhand’s land is forested and inhabited by 32 Scheduled Tribes Community and other forest-dwelling dependent communities.

“We work with the Santhal community as throughout history, they have endured displacement, migration and economic challenges,” says Narendra Kumar Mahto.

The Santhals in Hazaribagh, one of India’s largest tribal communities, have long relied on agriculture and forest-based livelihoods, sourcing food, fuel, and animal fodder from their environment. Fishing is also a traditional occupation. However, as the region developed, opportunities became scarcer, and the Santhals now face numerous challenges, including poverty, lack of education, and inadequate access to healthcare. As per the NFHS-5 data, a significant portion of children suffer from malnutrition with 31% stunted and 22% wasted. Additionally, anemia remains wide-spread affecting 63.1% of children. Non-communicable diseases like diabetes and hypertension are prevalent among the adult population, necessitating targeted healthcare interventions. This further has long-term impacts on education and overall well-being.

Industrial and mining activities have led to land alienation and displacement, exacerbating their socio-economic vulnerabilities. Despite various government initiatives, the benefits of development often fail to reach this marginalized community effectively. Between 2001 and 2011, Hazaribagh witnessed mass migration, with the working-age population moving to other states in search of better opportunities, leaving those who remained with even less access to resources. However, the pandemic reversed migration patterns in the state, causing its socio-economic system to be overwhelmed wherein almost 10 lakh migrants returned to Jharkhand with over 78 thousand who returned to Hazaribagh, further leaving them unemployed.

It is well known that the Santhal community in Hazaribagh has historically relied on forest land and its resources for their livelihood. In recognition of this, the Forest Rights Act of 2006 was enacted to grant access to forest land, as well as community and individual forest rights.

Jan Sahyog Kendra’s Role in Supporting Local Governance:

Narendra Mahto, widely known as ‘Rangeela,’ has worked extensively with indigenous communities in the Ttijhariya and Bishnugarh blocks of Hazaribagh – areas characterized by dense forests. During his awareness-building engagements, he discovered that the area lacked a forest map or any legal document to verify that the villagers were living in forest dwellings. As a result, Jan Sahyog Kendra (JSK) took a further step by collaborating with local governance structures at the panchayat or village level to ensure that the community gets access to their rights and entitlements as per the State.

“We have ensured that 43 individuals in Kharna–Bokaro get access to their Individual Forest Rights with adequate Government Support,”-Narendra Mahto states

A 20-kilometre journey brought us to Ttijhariya, a community development block renowned for its coal production and the sweet delicacy Gulab Jamun. Here, the Rebuild team met with the district staff of JSK amid a lush green forest of ‘sal’ trees.

The purpose of this meeting was to understand the extensive effort and time required to secure every individual’s “daava” or claim to forest land. The term “daava” refers to the formal and informal claims that communities make to secure their rights under the Forest Rights Act (FRA). This process is crucial for addressing the needs of the Santhal community in Hazaribagh, ensuring they have access to the land and resources essential for their livelihood.

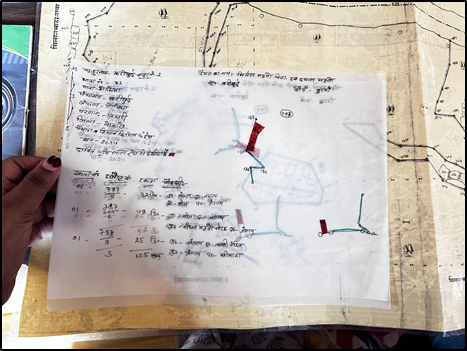

JSK works closely with the Gram Sabha and serves as an intermediary body that plays an active role in expediting this process. Their approach is to empower the community by providing tools to legitimize their claims. Through Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) training, JSK collaborates with the committee and the Forest Department to secure a forest map and draw individual claims to the land. The committee, established by the Gram Sabha, comprises 5 women and 10 men. A forest map provides clear documentation of land boundaries, defining the extent of land that a community or individual owns. It also shows evidence of long-term use and occupation by local communities, serving as legal evidence in land occupation and usage claims.

The entire process of identifying, selecting, and conducting meetings with the committee takes about three months per committee. With community mobilizers from within the community like Chunnu Murmu from JSK, this process becomes more effective and meaningful. Trust is easily built, as are the capabilities to engage with the State with knowledge and mutual respect. Once a forest map is procured from the Forest Department, individual maps for each claim are drawn, helping to define the exact extent of land that a community or individual owns. This meticulous process ensures that their traditional rights and livelihoods are safeguarded.

Forest mapping and other community support:

40 km from Ttijhariya, is Bokaro where in the Karrikhud Panchayat, the Rebuild team witnessed firsthand, the dedication and efforts of JSK’s on-ground team primarily comprised of the Santhal community mobilisers and facilitators. The forest map drawn by ‘Meena’ (often associated with the forest-dwelling communities’ customary rights and practices, specifically relating to their access and use of forest resources) serves as a tangible representation of the community’s connection to the land, supporting their claims and providing a basis for legal recognition and protection.

The creation of a forest map for each claim is not just a technical task but a crucial step in legitimizing the community’s claims to their ancestral lands. By documenting the boundaries and usage of the land as delineated by the State, JSK helps the Santhal community and other forest dwellers establish their legal rights and confidently apply for their claims.

In Karrikhud, we met with Prakash Hansada and Ramadhin Tiwari, two dedicated individuals meticulously crafting over 100 maps to support land claims legally. Both Prakash and Ramadhin commit to residing in each panchayat for 45-60 days, depending on its size, until every map is hand-drawn and attached to the respective claim. On average, they produce 4-5 maps per day, with each panchayat typically comprising around 200 individuals. Their efforts ensure that each claim is backed by precise, legally recognized documentation, highlighting the importance of their work in securing the community’s rights to their land.

In Gomiya, Bokaro, the Rebuild team observed the diligent efforts of JSK in securing land rights for the Santhal community. JSK’s role, however, goes beyond creating forest maps. The organization works closely with adolescent groups within the community to gather and compile necessary documents for submission to the Gram Sabha.

The Gram Sabha organizes meetings with the Forest Department/Van Adhikar Samiti to present the forest map. These meetings are held every 15 days, and if the Forest Department members miss two consecutive meetings, the Gram Sabha can forward the applications directly to the SDLC for further action. This entire process takes close to 2-3 months and requires multiple follow-ups. Through this process, JSK in its decade-long work has secured 560 acres of forest land.

A few roadblocks along the way:

Despite these efforts, some challenges persist in delivering claims effectively. One of the most prominent issues observed in these villages is heavy migration due to a lack of local opportunities for livelihoods. Many homes are locked after the harvesting season as villagers’ families leave in search of employment opportunities elsewhere wherein metropolitan cities as construction workers. As a result, some migrants may miss out on securing their Individual Forest Rights. To address this, JSK ensures that migrants provide their information through an application called ‘Geet,(Entitlement Tracking System)’ which keeps all their details organized to minimize the risk of exclusion.

Additionally, the process of securing land rights requires extensive documentation, including at least 2 out of 13 multiple address identity proofs. Despite the number of options available, due to a history of displacement and migration, many community members may not have these documents, causing some individuals to be overlooked in the process. Moreover, since this entire process requires a lot of manual paperwork, there are unanticipated delays. For instance, JSK works with over 50 Panchayati Raj Samiti and there is a chance that some may get missed out in the process.

JSK is working to strengthen the governance structure at the Gram Sabha level by working with the Forest Department to expedite the process by improving engagement and knowledge. Through efforts in selecting and training community members especially youth, JSK continues to ensure the Santhal community crafts its journey towards realizing its entitlements through the National Forest Rights Act.

Finding a small pool of water can go a long way:

In the Gomiya block of Bokaro, finding a water source in summer once seemed impossible. The community struggled, with women, men and children walking long distances to collect water for their daily use, consuming time and physical energy. In the midst of this, JSK with the support of community members discovered a small spring in the middle of the forest. Recognizing its potential, the community came together to protect the spring, forming a small well-like structure or “daadi” that ensured a continuous flow of water. a single freshwater source in the village now provides for 52 households and neighbouring field areas.

This water is clean enough that it can be used for drinking. This has significantly reduced the daily burden on women, saving time and effort. Other such structures are being identified as protected and constructed in the block. In addition to this, JSK has also undertaken the restoration of ponds, which are either individually owned or belong to the entire village.

A pond that measures approximately 100×150 feet can provide 1-1.5 lakhs of income through fish farming per season. During the restoration process, a ‘Paani Samiti’ is formed to oversee the efforts. JSK invests approximately 20-25K per pond to purchase fish or ‘beej’ (called seeds locally), while community members contribute their labour to clean and manage the pond.

The cleaning process takes about 5-6 weeks. In the first two weeks, community members add limestone (chuna) to eliminate bacteria. This is followed by the application of 7-8 kgs of mustard cake (sarson ki khalli) as an organic fertilizer and then 10 kgs of fresh raw manure. After these preparations, the community members introduce fish, primarily Rohu, into the pond. This initiative not only restores the ponds but also provides a livelihood for the community. Within 8-9 months, the initial investment of 20-25K yields a return of 1-1.5L, which is then divided among the members of the Paani Samiti. JSK actively works to ensure the equitable distribution of these funds, although this sometimes can be challenging.

By the community, for the community:

JSK has formed young adolescent groups that further promote education by teaching children in classes 1-5, these children are unable to gain any formal education due to a lack of resources. In addition to this, JSK has formed Self Help Groups (SHGs) with the vision to link every family member to the ‘Phulo Jaano Yojana’– an initiative of the Government of Jharkhand. The scheme is designed to promote sustainable livelihood opportunities for women who are associated with selling and manufacturing liquor. Through this scheme, women are provided with an interest-free loan and encouraged to start an alternative livelihood source of their own. It is to be noted that not many are aware of this scheme and women often lose out on the opportunity to start afresh with an alternative livelihood. JSK is encouraging livelihoods in sustainable fishing and agriculture.

Backing the Frontline:

JSK was one of the organizations that was supported during the Back the Frontline (BTF) initiative (pre-cursor to Rebuild) wherein, 152 organizations were supported and it was heartening to see how the BTF fund, released in 2020 is still relevant to the community 4 years down.

Apart from distributing immediate relief and ration items, JSK also set up 15 ration shops that are being run by the local Santhal women in villages that were over 100 kilometres away from the district headquarters. The shops are popular, and the women have diversified to sell petrol, chicken and rations earning 1-1.5 lakhs per annum from their stores. These are also convenient for the communities residing in these villages who would otherwise have to walk up to 15-20 kilometres one way to purchase these from the main market.

Next steps for JSK:

Understanding the criticality of long-term sustainability, JSK is currently focused on expanding its operations in water conservation and working on getting more access to rights and entitlements by extending these efforts to more villages. Looking ahead, the organization plans to introduce new initiatives such as lac farming and expand projects on fish-rearing with a larger vision of creating sustainable livelihood sources.