“All the kids came running to me and told me, ‘Aunty, Chandni’s mother has married her off” – narrates Paramita. Chandni Sahney is one of the many children who Paramita started working with in the Kalighat red light area of Kolkata. Chandni was visiting her maternal home in Bihar, when she was forced to marry at the age of 14.

Towards the end of the 1990s, community-based interventions within red light areas were rare, where the primary focus was on building shelter homes for children living in red light areas to avoid forced entry into sex work. However, once a girl was out of the shelter home at the age of 16 (prior to the introduction of the Juvenile Justice Act) they would find themselves in the very same areas yet again, vulnerable to the very same oppressive societal constructs, which would force them into early marriage. Marriage was one of the key contributors to a phenomenon of forced backdoor trafficking into the sex trade, usually perpetrated by their own husbands. Paramita Banerjee, a MacArthur fellow for Leadership Development who started working in Kalighat, had a crucial realization that would then go on to define the work she would do for decades to come—

“Red light areas are always seen as a destination where one ends up post sex-trafficking, we needed to shift this and start thinking how it could potentially be a source point of where it all begins. And the number and presence of child care institutions will never be proportionate or contextualized to the needs and unique vulnerabilities of the children living in these areas.”

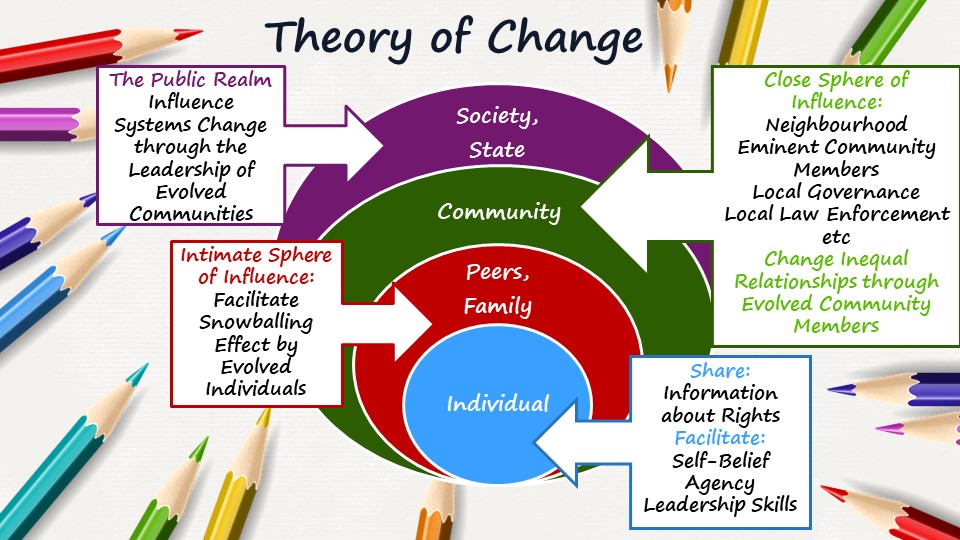

With this thought, DIKSHA came into being in 2001 with a focus on training and capacitating children themselves to break through an inter-generational cycle of sex work. This defines the origin of a model that DIKSHA has since continued to adapt across their work over the last two decades –placing children and youth at the core of DIKSHA’s work while creating deep and sustained impacts within their various spheres of influence.

“Aunty, I am the only girl in the village who has studied until the 8th grade, but I’m going to change that.” – Chandni told Paramita on her first visit back to Kalighat after getting married. Even with all existing societal constructs in place, Chandni continues to champion girl’s education in her husband’s village in Bihar.

Sustainability and Growth

DIKSHA started its journey working in Kalighat and has now expanded into a total of 3 red light areas and 2 quasi red light areas in the region. Quasi-red light areas are localities from where women travel to red light areas for sex work. Having replicated their model across and addressing varying degrees and kinds of vulnerabilities associated with each of these areas, DIKSHA is aiming to gradually phase out and hand over all interventions to the community. DIKSHA’s first formal exit was from Kalighat where they handed over all programmatic operations to Tumpa Adhikary, a community leader who has grown up in the area and has been with DIKSHA since she was 12 year’s old.

With this, it is now their vision to continue their journey of enabling individual change agents across other varying contexts and regions – influencing their decision to step into regions within rural districts in West Bengal – Birbhum, Murshidabad, Nadia and North 24 Parganas. As part of our visit to the organization, we had a chance to observe DIKSHA’s process of building out their engagement with communities in Birbhum – in a region called Bolpur, where DIKSHA is using sports a medium of change for young girls and women.

Football and Gender

Bolpur is a space of immense cultural and historical significance to the people of West Bengal – the exquisite Kantha stitch embroidery, the eminent Vishwa Bharati University set up by Rabindra Nath Tagore, the popular Shonajhuri Haat (a street market for local handicrafts). Amidst all of Shantiniketan’s glory, one might overlook the fact that this is also an extremely economically impoverished district and has amongst the highest rates of child marriage in the country. For an organization like DIKSHA that is now trying to raise funds for their interventions in the region, this paradox of Bolpur poses many layers of challenges.

In Bolpur’s Kamarpara village, we had a chance to visit Jhuma’s home. Jhuma and her friends who also came to visit us are women of the Kamarpara village, all skilled at the Kantha stitch embroidery.

“After we’re done with our household chores, we all get together to stitch whenever we get any order from the city. This is intricate work and takes a lot of time and effort to complete but we do it because all of us enjoy working together. For stitching an entire bedsheet which took the four of us a month to make, we were paid INR 2000, which we divided amongst ourselves. But we really enjoy working with each other.” – says Jhuma.

For context, such bed sheets are sold in the market for INR 6000-8000, and possibly higher if the work is very intricate. Jhuma earned INR 500 for it over a month, which is less than INR 20 per day. The DIKSHA team says about this— “There are two layers to this – one is of course the exploitation and unfair wage practices given the lack of alternate livelihood opportunities. The other is that such taxing, tiring, underpaid work after a whole day of household chores is how someone like Jhuma defines leisure.”

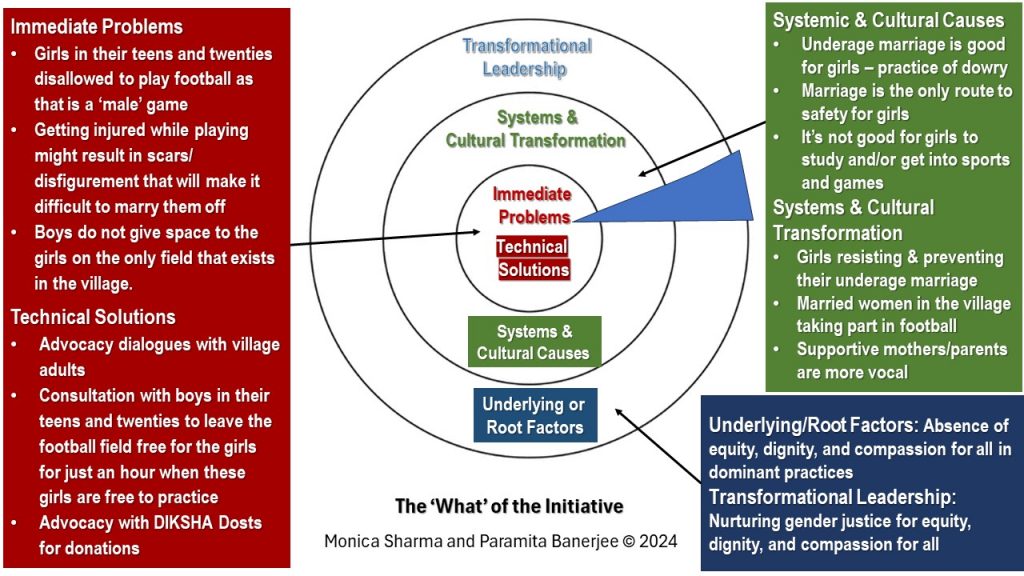

West Bengal has always had a thriving culture of ‘para clubs’ – a physical space in every locality where people (typically men) gather for adda (chats and discussions), carrom, and most importantly unite for their shared love of football. In the Kamarpara and Ahmadpur villages of Bolpur too, men and boys who have been fascinated by the sport for years – but what is exceptional is that they’ve chosen to use their skills in football to train girls from their own and adjacent villages in the game.

DIKSHA’s journey in Bolpur started when a group of girls approached Lopa (who leads operations) and Paramita (who they now call Pishidida/Aunt+Grandma), to intervene as boys on the field and local community members would prevent them from playing on the field. “From our work in Kolkata, we knew that DIKSHA only needs to create an ability for the girls to speak for their own self – expression and impact are the same”, they say.

DIKSHA with Kamarpara Girl’s Football Team

DIKSHA’s work in sports for change is in many ways an extension of their interventions in Kolkata. One where they are aiming to empower individual girls, while engaging their different spheres of influence – their families who despite initial resistance have now been encouraging the girls to play and the men and boys in the village who have now become coaches. The Kamarpara girl’s football team, with Basubeb, Prabhat, Samar and Arjun’s support, have been on the field for over two years now.

DIKSHA is now trying to ensure that there is a holistic ecosystem that exists in the village— young women and girls play football and build their confidence, respected male members publicly champion these efforts, and women are able to avail diverse livelihood opportunities for economic agency.

In a candid conversation, Paramita asks Jhuma and her friends (adult daughters and daughters-in-law of the village) if they would like to play football like their daughters– they all smile and respond – “If we are allowed to then why not, we’ve never gotten a chance before! But it’s unlikely that anyone will let us.” It is important to understand that for DIKSHA, football is not the goal in itself, it is a medium of change to shift societal structures. “If you scale deep enough, you will create a paradigm shift in ways such that some societal practices will never be seen again,” Paramita tells us.

The story in Ahmadpur village (which is 20 kilometers away from Kamarpara) is similar yet different. Ahmadpur is a Santhal tribal region where their coach Bishu da had already managed to put a team together, and reached out to DIKSHA with bigger dreams for the Ahmadpur Girls Football Team.

Ahmadpur Girls Football Team

“I wake up at 4:30 in the morning to finish all household chores” says Shivani (captain of the football team). “I am up by 5 because I need to work on the field” says Jayanti who works as agricultural labour. “I work at a grocery store my family runs” says Hanshi who has the most endearing name for Paramita – ‘bondhu’ (which literally translates to friend). “I used to work at a factory that makes plastic banners, I have stopped going there now”, says Saraswati who is a passionate reader. The girls shared their daily routines with us, one after the other, and what tied them all together was this – “At 4:00 in the evening we are all on the field for practice”.

Another thing that is in common in all of their expressions is how much they all adore Sumitra didi – who is at the core of the team coming together. Sumitra was amongst the first girls who Bishu da started to coach but was forced to stop playing football after she got married. “I never knew marriage meant being away from the thing I love the most, I could never imagine my life without football. I will ensure that this is not what the future of the other girls in the team looks like. Our families may support us but society does not”, says Sumitra.

Sumitra and her football coach Bishu

The conversations with the football teams and the different members of DIKSHA put into perspective why building change agents and enabling a larger value based systems change continues to lies at the core of DIKSHA’s work – be it in red light areas of Kolkata or in villages of Birbhum.

The way forward

While the criticality of the work that grassroots organizations is often discussed, it is important to reflect back on what it has taken and will take for an organization like DIKSHA to continue the work they are doing. Over the next few years, DIKSHA aims to stabilize its football work with funding support; put in place mechanisms for further leadership development within the organization; and document its journey and stories from over 2 decades to share with the larger sector a holistic, evidence based replicable model of community led change.